As good an ending as any.

Review at New York Times.

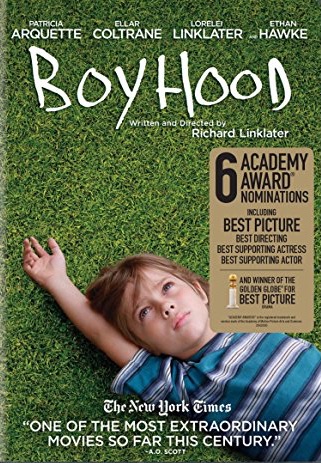

Oh those rave reviews:

Coltrane, who will turn 20 in August, has spent almost all his life here in “keep it weird” Austin — mostly home-schooled except for three years of high school, followed by a GED; landscaping work for his stepfather; photography and painting in the trippy vein of Alex Grey; and the slow-burn emotional time bomb of a movie formerly known as “The 12-Year Project.” Linklater’s deep-focus, pseudo-vérité coming-of-age story was designed to capture a fictional family in messy real time — the mutable boy, Mason (Coltrane); his straight-A sister, Samantha (Linklater’s daughter, Lorelei); and their divorced parents (Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette). Every year before the usually four-day-long shoot, Linklater would hold a week of rehearsals, dinners, and collaborative rewrites — a process also used in Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight. Hawke, who was in those too, compares it to the improv-plus rewriting approach of Mike Leigh. “We all used this fictional family as a crucible,” he says, “in which to pour our collective thoughts on growing up.”

But Linklater’s film isn’t just an aesthetic gambit. It’s also a psychological experiment, absorbing the personalities and dramas of its stars and, 12 years later, showing them — and then the world — a fictional doppelgänger of their lives. – Vulture.com

Exams are

Bring laptop with

Basics

Make a 2 – 3 minute documentary, using as much or as little of the provided video clips and sound files as you want to make a compelling piece (but not a montage). There is no need to match the voice-overs to the visual – they can just track along separately.

Required

Basics, hand drawn:

Basics, typeset in a word processor:

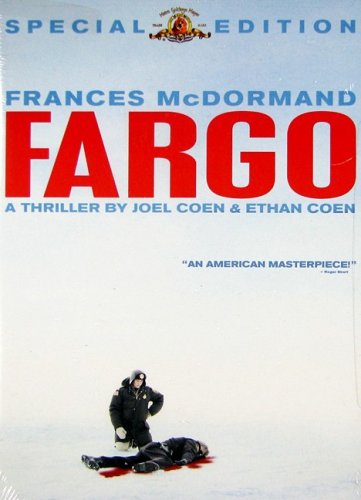

Roger Ebert – “[Fargo] rotates its story through satire, comedy, suspense and violence, until it emerges as one of the best films I’ve ever seen. To watch it is to experience steadily mounting delight, as you realize the filmmakers have taken enormous risks, gotten away with them and made a movie that is completely original, and as familiar as an old shoe – or a rubbersoled hunting boot from Land’s End, more likely.”

Film blogger Kinosaur has a nice theory on what’s up with Mike Yanagita, a seemingly out-of-the-blue character.

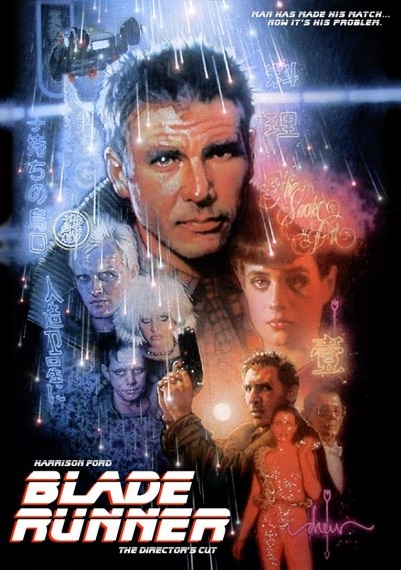

It’s 2018, a year away from Blade Runner. How close are we to building Nexus 6?

Most film noir movies don’t use the flashback/voice-over technique of storytelling, but this technique has become closely associated with film noir for two main reasons.

One is that a few of the most iconic noirs do make use of it, so people who have only seen a handful of the true classics are more likely to associate this technique with noir. The other, and I’ve never seen this commented on elsewhere, is that the use of a voice-over closely replicates the tone and feeling of the novels on which a lot of noir movies were based.

The Philip Marlowe detective novels by Raymond Chandler are all narrated in the first person by the detective himself, and his world-weary voice and cynical commentary create much of the noir mood in the books. So when a film noir uses a flashback narrated by the detective, it produces basically the same feeling. It makes the movie feel more like the book.

Another aspect is that the flashback in a film noir is usually leading up to a tragedy of some kind. It’s the story of one man’s fall from grace. So the voice-over has a built-in quality of regret and pathos, as the person speaking has already experienced the tragedy. That’s why the theatrical version of the 70s sci-fi noir classic “Blade Runner” feels even more noir than the otherwise superior director’s cut, which dispenses with the voice-over. The studio insisted on adding the voice-over to help the viewers understand a complex story, but in doing so they inadvertently tapped in to a powerful noir trope – the voice of a doomed man narrating the story of his own defeat.

From The Blade Cuts, an interview with Ridley Scott:

Scott: …did you see the version [of the script] with the unicorn?

McKenzie: No…

Scott: I think the idea of the unicorn was a terrific idea…

McKenzie: The obvious inference is that Deckard is a replicant himself.

Scott: Sure. To me it’s entirely logical, particularly when you are doing a film noir, you may as well go right through with that theme, and the central character could in fact be what he is chasing…

McKenzie: Did you actually shoot the sequence in the glade with the unicorn?

Scott: Absolutely. It was cut into the picture, and I think it worked wonderfully. Deckard was sitting, playing the piano rather badly because he was drunk, and there’s a moment where he gets absorbed and goes off a little at a tangent and we went into the shot of the unicorn plunging out of the forest. It’s not subliminal, but it’s a brief shot. Cut back to Deckard and there’s absolutely no reaction to that, and he just carries on with the scene. That’s where the whole idea of the character of Gaff with his origami figures — the chicken and the little stick-figure man, so the origami figure of the unicorn tells you that Gaff has been there. One of the layers of the film has been talking about private thoughts and memories, so how would Gaff have known that a private thought of Deckard was of a unicorn? That’s why Deckard shook his head like that [referring to Deckard nodding his head after picking up the paper unicorn].

Commentary at

“This Is America” is currently being analyzed on Twitter as if it were the Rosetta Stone. The video has already been rapturously described as a powerful rally cry against gun violence, a powerful portrait of black-American existentialism, a powerful indictment of a culture that circulates videos of black children dying as easily as it does videos of black children dancing in parking lots. It is those things, but it also a fundamentally ambiguous document. The truth is that this video, and what it suggests about its artist, is very difficult. A lot of black people hate it. Glover forces us to relive public traumas and barely gives us a second to breathe before he forces us to dance. There is an inescapable disdain sewn into the fabric of “This Is America.” The very fact that the dance scenes are already being chopped into fun little GIFs online, divorcing them from the video’s brutality, only serves to prove his point.

Read and watch:

Watch (maybe make one of these for your final film – interview somebody, add visuals w/o showing the interviewee):

Watch (so perfectly reductive):

Lindsay Ellis is kind of a god among YouTube filmsters. She has an academic background (MA, USC film school), but usually has a very light touch as she explains/deepens things. I can’t remember if we followed up watching Mad Max: Fury Road with her piece on Planting and Payoff – if not, watch it. (Recently she’s been assaulting The Hobbit, trying to explain why it was soooo bad.)

But for today, finish the period with her very-academic and yet very-true and -needful explanation of 3-act structure in film. It is really the way almost everything is built.